Darwin, Gardiner & the Fuegians

(Copyright Creation Matters, Vol. 22, No. 2, March/April, 2017.)

As 2016 came to a close, I had the opportunity to visit the “bottom of the world” (southern Chile, Argentina and even Antarctica). I was struck with the natural beauty of Patagonia, where the birds fly north for the winter. Tierra del Fuego’s picturesque islands, Antarctica’s glistening white sculptures, the massive unafraid flocks of penguins, the soaring Andes, and the rugged people all made the trip unforgettable. But the story of European contact with the native Fuegians captivated my attention like very few have ever done. It is the tale of natives, who had lived their lives in constant warfare, fear, and superstition, coming to Christ. It is a story of the Lord garnering “his praise from the end of the earth” (Isaiah 42:10).

As 2016 came to a close, I had the opportunity to visit the “bottom of the world” (southern Chile, Argentina and even Antarctica). I was struck with the natural beauty of Patagonia, where the birds fly north for the winter. Tierra del Fuego’s picturesque islands, Antarctica’s glistening white sculptures, the massive unafraid flocks of penguins, the soaring Andes, and the rugged people all made the trip unforgettable. But the story of European contact with the native Fuegians captivated my attention like very few have ever done. It is the tale of natives, who had lived their lives in constant warfare, fear, and superstition, coming to Christ. It is a story of the Lord garnering “his praise from the end of the earth” (Isaiah 42:10).

The Beagle Voyages

In 1826, HMS Beagle, under the command of Captain FitzRoy, was sent to explore the coast of South America. Having discovered the Indians of Tierra del Fuego, he took four natives with him back to England. After being introduced to the wonders of 19th century England for two years, the Fuegians were again taken onto the Beagle, this time to be taken home. Aboard this same ship, for its second voyage to Tierra del Fuego, was the young naturalist Charles Darwin. After a voyage of about a year, the crew safely returned the South American natives to their home. But the Fuegian tribes made a lasting negative impression on Darwin.

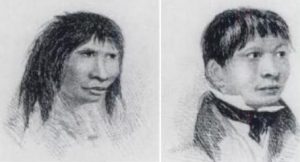

Jemmy Button, from FitzRoy, R., Narrative of the surveying voyages of His Majesty’s Ships Adventure and Beagle, 1839, Vol. 2.2.

“These poor wretches were stunted in their growth, their hideous faces bedaubed with white paint, their skins filthy and greasy, their hair entangled, their voices discordant, their gestures violent and without dignity. Viewing such men, one can hardly make oneself believe they are fellow-creatures, and inhabitants of the same world. It is a common subject of conjecture what pleasure in life some of the less gifted animals can enjoy: how much more reasonably the same question may be asked with respect to these barbarians” (Darwin, 1840).

It seemed that as soon as the three Fuegians were back amongst their own people, they resorted to their native ways. After 15 months of researching coastal South America, the Beagle stopped once again at Tierra del Fuego. Only one of their native companions could be found, a young man who had been christened “Jemmy Button.” But even Jemmy had returned to being a “wild-looking savage,” naked except for a loin cloth. Darwin noted this complete failure to “civilize” the Fuegians.

Moreover, Darwin’s limited exposure to the Fuegian language left him unimpressed. They seemed to him to repeat the same phrases over and over again, and he theorized that their whole language was limited to 100 words (Bridges, 2007). So, Darwin concluded that the Fuegians were “missing links” and, in his book Descent of Man, he cited the Fuegians as evidence that “man is descended from a hairy, tailed quadruped” claiming that the “Fuegians rank amongst the lowest barbarians…”(Darwin, 1871).

Enter Allen Gardiner

From earliest childhood, Allen Gardiner was thrilled by stories of adventure and strange lands. When he was 14, Gardiner left home entered the Naval College at Portsmouth, England. Though he had an exciting career in the British Royal Navy, it seemed that God had bigger plans for him. He accepted Christ as Savior while in the Navy and became an avid Bible reader. Soon Gardiner became acutely aware of the Lord’s desire to be glorified among all nations. He ended his naval career in 1826 to pursue evangelistic work “unto the uttermost part of the earth” (Acts 1:8).

From earliest childhood, Allen Gardiner was thrilled by stories of adventure and strange lands. When he was 14, Gardiner left home entered the Naval College at Portsmouth, England. Though he had an exciting career in the British Royal Navy, it seemed that God had bigger plans for him. He accepted Christ as Savior while in the Navy and became an avid Bible reader. Soon Gardiner became acutely aware of the Lord’s desire to be glorified among all nations. He ended his naval career in 1826 to pursue evangelistic work “unto the uttermost part of the earth” (Acts 1:8).

Gardiner felt called by God to reach Indian tribes in South America. His first effort was in the Andes mountains in 1838. He crossed the mountains on muleback to reach remote indigenous tribes. But all of his evangelistic attempts there failed. Then in the early 1850s, Gardiner and six other men attempted to reach tribes in Patagonia, the entire region comprising the southern tip of South America, including Tierra del Fuego. The team included a surgeon by the name of Richard Williams, a young Bible teacher named John Maidment, a carpenter, and three strong Christian fishermen. These Anglican missionaries had learned about the Fuegian tribes because of the four natives brought to England by Captain Fitzroy on the HMS Beagle.

The ship HMS Ocean Queen transported Gardiner and the others to South America, dropping them off on Picton Island. Their sole mission was to bring the word of God to the Yahgan Indians of Tierra del Fuego. Gardiner hoped to find Jemmy Button to help with translation. Immediately upon arriving, serious problems arose. As their ship sailed away, they realized that they had forgotten their stock of gun powder. Then they failed to locate Button, and the Fuegians that did come to meet them became increasingly hostile, wanting to steal all their possessions.

Rather than fight the Indians, the missionaries loaded their small sailboats, saving what they could, and sailed away from Picton. The Fuegians chased Gardiner incessantly with their canoes. Finally, the team found protection in Spanish Harbor of Tierra Del Fuego. But it was a rough, unforgiving location, and one of their sailboats was destroyed on landing. Lack of food quickly led to health problems. An unusually high wave splashed into the cave where they were living, taking almost everything with it, including their Bibles. A very harsh winter followed. One by one, the missionaries succumbed to the elements. Gardiner’s journal contained the prayer “Let not this mission fail!” and another plea, “Grant O Lord, that we may be instrumental in commencing this great and blessed work…” (Brown, 1866)

In January, 1852 the British ship HMS Dido found the small sailboat and the dead missionaries. The crew buried Gardiner and rescued his water-soaked mission diary. Since all of the missionaries had died of hunger, cold, and sickness, one would expect the dominant themes of Gardiner’s journal to be grief and despair. But remarkably, Gardiner’s words radiated a contagious joy. When he was in the final stages of starvation, he was focused on the future. He coined a new name for his mission society. He proposed that the Patagonian Missionary Society should expand its field of work to the entire continent and be renamed the South American Missionary Society (SAMS).

In January, 1852 the British ship HMS Dido found the small sailboat and the dead missionaries. The crew buried Gardiner and rescued his water-soaked mission diary. Since all of the missionaries had died of hunger, cold, and sickness, one would expect the dominant themes of Gardiner’s journal to be grief and despair. But remarkably, Gardiner’s words radiated a contagious joy. When he was in the final stages of starvation, he was focused on the future. He coined a new name for his mission society. He proposed that the Patagonian Missionary Society should expand its field of work to the entire continent and be renamed the South American Missionary Society (SAMS).

As Gardiner died, his heart seemed to overflow with thanksgiving for God’s many mercies. “Great and marvelous are the loving kindnesses of my gracious God. He has preserved me hitherto, and for four days, although without bodily food, without any feelings of hunger or thirst” (Prichard, 2001). Dr. Richard Williams, the physician of the missionary team, described the same peace that passes understanding. He wrote from “Pioneer Cave” these remarkable words shortly before his passing: “Should anything prevent my ever adding to this, let all my beloved ones at home rest assured that I was happy beyond all expression the night I wrote these lines, and would not have changed situations with any man living. Let them also be assured that my hopes were full and blooming with immortality; that heaven and love and Christ, which mean one and the same divine thing, were in my heart; that the hope of glory, the hope laid up for me in heaven, filled my whole heart with joy and gladness, and that to me to live is Christ, to die is gain. I am in a strait betwixt two, to abide in the body, or to depart and be with Christ, which is far better.

…I am happy day and night, hour by hour. Asleep or awake, I am happy beyond the poor compass of language to tell. My joys are with Him whose delights have always been with the sons of men, and my heart and spirit are in heaven with the blessed. I have felt how holy is that company; I have felt how pure are their affections; and I have washed me in the blood of the Lamb, and asked my Lord for the white garment, that I, too, may mingle with the blaze of day, and be amongst them one of the sons of light. Much more could I add, but my fingers are aching with cold, and I must wrap them up in my clothes; but my heart, my heart is warm, warm with praise, thanksgiving, and love to God my Father, and love to God my Redeemer” (Brown, 1866).

When news of the missionaries’ deaths reached England, the London Times carried a critical editorial decrying the loss of life and resources for so foolish a cause. However, the story of the missionaries’ deaths caught the attention of the nation, and a book on their mission, which included Gardiner’s journal, was a bestseller. Biblically-minded churchmen responded to the criticism of the mission with contributions to the South American Missionary Society (SAMS). New missionaries were recruited and a second team planned to set out in 1859. Their schooner was christened the Allen Gardiner. This team was better equipped. Using the Falkland Islands as a base, the missionaries first took time to learn a bit of the Fuegian language.

Another Setback

Armed with rudimentary linguistic skills, eight missionaries were prepared to contact the Fuegians. The Allen Gardiner landed in Tierra del Fuego and initial outreach began. But during a Sunday service on shore, the missionaries suddenly found themselves under attack. Within minutes, all eight missionaries were clubbed and speared to death by covetous, rowdy natives (including the jealous Jemmy Button). Only a cook who stayed aboard the ship survived. The field director of SAMS, George Despard, who was stationed at the Falklands, was crushed by the loss of this second missionary team. Two missionary teams had gone out with high hopes, and the results were 15 dead, 7 by starvation and 8 murdered by the Fuegians. All seemed to be lost.

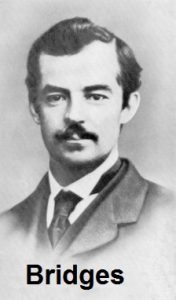

But 17-year-old Thomas Bridges, who had been stationed in the Falklands, volunteered to remain behind and carry on. His surname was given because he was found as a baby, abandoned on a London bridge. Despard had taken Thomas in and reared him as his own child. Bridges remained in the Falklands and eventually traveled back to Tierra del Fuego alone. Because of his complete vulnerability and his command of the Fuegian language, the natives allowed Thomas into their settlements. They eventually were moved by the forgiveness and kindness that he showed. In the subsequent years. Subsequently Bridges baptized many of the same people who had killed his friends. After decades of faithful service, the SAMS team would see nearly the whole Yahgan tribe turn to Christ. Moreover, Bridges authored a Yaghan-English Dictionary, which contained 32,000 words (Bridges, 2007). It turned out that the Fuegian language was far more complex and precise than English!

But 17-year-old Thomas Bridges, who had been stationed in the Falklands, volunteered to remain behind and carry on. His surname was given because he was found as a baby, abandoned on a London bridge. Despard had taken Thomas in and reared him as his own child. Bridges remained in the Falklands and eventually traveled back to Tierra del Fuego alone. Because of his complete vulnerability and his command of the Fuegian language, the natives allowed Thomas into their settlements. They eventually were moved by the forgiveness and kindness that he showed. In the subsequent years. Subsequently Bridges baptized many of the same people who had killed his friends. After decades of faithful service, the SAMS team would see nearly the whole Yahgan tribe turn to Christ. Moreover, Bridges authored a Yaghan-English Dictionary, which contained 32,000 words (Bridges, 2007). It turned out that the Fuegian language was far more complex and precise than English!

The most dramatic demonstration of the change in the people whom Darwin had labeled as the lowest form of man, took place when an Italian ship was sinking offshore from Fuegian territory. Formerly, the Fuegians would most likely have killed the sailors and helped themselves to booty. But as followers of Christ, the Fuegians risked their lives to rescue these complete strangers. The King of Italy was so moved by their heroism that he had a medal struck in their honor, and in honor of Bridges and SAMS. Darwin himself was so impressed with the change in the Fuegians that he became a financial supporter of SAMS for the rest of his life. So, while Darwin drifted towards atheism and wrote about evolution, one wonders how he would have responded to the query: What power would your naturalistic worldview and evolutionary teachings have offered to transform these darkened, hopeless people?

Lesson Taught

Through the gospel, the Fuegians were transformed into being a people whose heroism and altruism were internationally acclaimed. This missionary story teaches us that we all have an important role to play in God’s work and that ultimate success or failure doesn’t depend on us. Allen Gardiner was greatly used by God, despite apparent failure. We should walk in faith such that our joy is dependent only on our relationship with God, not on our circumstances or the apparent fruitfulness of our efforts. While Christians ought to do their best to plan, we must resign to the fact that God may perform his work quite differently from what we expect. “As the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways and my thoughts than your thoughts” (Isaiah 55:9).

What God accomplished in Tiera del Fuego went far beyond what the missionaries had expected, but at a far higher cost than anyone expected. In retrospect, we can see that:

- Without their starvation, Gardiner and his companions couldn’t have shown Christendom the depth of Christian joy amid fruitless service.

- Without the murder of his missionary peers, Bridges couldn’t have shown the radical nature of God’s forgiveness to the natives.

- Without the storm at sea, the Fuegian Christians couldn’t have shown the world God’s rescuing love that had taken up residence in their hearts.

When things go wrong, we are tempted to think that God has failed us, or that evil has triumphed over good. But God may be bringing about fruit of a more enduring quality than that which is born in the placid seasons. Starvation, murder, and storms provided the canvas on which God painted a self-portrait, revealing His joy, forgiveness, and rescuing love. When we face setbacks, we need to cling to the knowledge that the Lord is still at work, even though we may not be able to see how. “Then said Jesus unto his disciples, if any man will come after me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross, and follow me” (Matthew 16:24).

References:

Bridges, E.L. 2007. Uttermost Part of the Earth: A History of Tierra del Fuego and the Fuegians. New York: The Rookery Press, pp. 34-35.

Brown, T. 1866. Life of Captain Allen Gardiner, the Founder of the Patagonian Mission. Mission Life, Vol. 1, pp. 404–405.

Darwin, C. 1840. Journal of Researches into the Geology and Natural History of the Various Countries Visited by H.M.S. Beagle Under the Command of Captain FitzRoy, R.N. from 1832 to 1836. London: Henry Colburn, pp. 235–236.

Darwin, C. 1871. Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, Volume 2, p. 34, 591.

Jardine, N., J.A. Second, and E.C. Spary. 1996. Cultures of Natural History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 335.

Prichard, T. (2001, August). 150th anniversary of the Death of Our Founder, Captain Allen Gardiner. Executive Director’s Letter, The South American Mission Society (SAMS).