The Zuiyo-Maru “Catch”

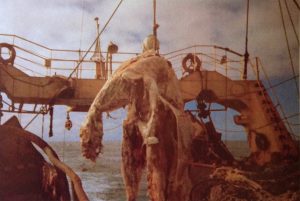

In April of 1977 a Japanese fishing vessel named the Zuiyo-Maru was traveling off the coast of New Zealand, when a large carcass became snarled in its nets. The rotting remains, weighing about 4,000 pounds, were hoisted up above the deck. Several pictures were taken a sample of horny fibers was preserved before it was cast back to sea so as to not spoil the mackerel catch. The drawing by Michihiko Yano, a crew member with some biology training, depicts a plesiosaur (bottom right), as does a commemorative Japanese stamp that was issued in 1977. The tissue sample taken from the carcass was studied by a team of Japanese scientists. Initially, the scientists at the Science Museum of Tokyo unanimously declared that the creature was a plesiosaur. But after a French team became involved, a 1978 Japanese symposium report stated that, while the identity of the carcass could not be determined with certainty, the carcass was most likely that of a large basking shark. The paper is quite dismissive of Yano, even though his educational qualifications and experience were superior to some of those that disparaged his finding.

In April of 1977 a Japanese fishing vessel named the Zuiyo-Maru was traveling off the coast of New Zealand, when a large carcass became snarled in its nets. The rotting remains, weighing about 4,000 pounds, were hoisted up above the deck. Several pictures were taken a sample of horny fibers was preserved before it was cast back to sea so as to not spoil the mackerel catch. The drawing by Michihiko Yano, a crew member with some biology training, depicts a plesiosaur (bottom right), as does a commemorative Japanese stamp that was issued in 1977. The tissue sample taken from the carcass was studied by a team of Japanese scientists. Initially, the scientists at the Science Museum of Tokyo unanimously declared that the creature was a plesiosaur. But after a French team became involved, a 1978 Japanese symposium report stated that, while the identity of the carcass could not be determined with certainty, the carcass was most likely that of a large basking shark. The paper is quite dismissive of Yano, even though his educational qualifications and experience were superior to some of those that disparaged his finding.

But numerous questions remain, including the observed large hind fins. The final report itself states: “The surface of the body was whitish and covered with dermal fibres which intersected each other like in whales and other mammals, but were not weak as in fish. There were thick, white, fat-like tissues on the back, and reddish muscles were seen running longitudinally beneath the white tissues. The putrefactive smell was not like that of teleostean fishes or sharks, but resembled that of marine mammals…. The head was said to have been hard, exposing the cranium, and not shark-like…. Unlike sharks, in which the nares [i.e. nostrils] are situated in the lower surface of the skull, the carcass had nares at the front end of what remained of the cranium.” Basking sharks do not have nostrils on the front of their head, nor do they have red meat and white fat. It would seem also that this scenario was different from the various decayed shark carcass sightings to which the scientists have compared it. Those other dead sharks floated ashore, while the Zuiyo Maru carcass was found 30 miles off the coast opposite Christchurch and was trawled off the bottom at a depth of 900 ft. The primary evidence given in favor of the basking shark identification was an analysis of the chemical composition of the horny fibers in the tissue sample. They matched elastoidin from a known basking shark. But the horny fibers are not themselves found in sharks!

But numerous questions remain, including the observed large hind fins. The final report itself states: “The surface of the body was whitish and covered with dermal fibres which intersected each other like in whales and other mammals, but were not weak as in fish. There were thick, white, fat-like tissues on the back, and reddish muscles were seen running longitudinally beneath the white tissues. The putrefactive smell was not like that of teleostean fishes or sharks, but resembled that of marine mammals…. The head was said to have been hard, exposing the cranium, and not shark-like…. Unlike sharks, in which the nares [i.e. nostrils] are situated in the lower surface of the skull, the carcass had nares at the front end of what remained of the cranium.” Basking sharks do not have nostrils on the front of their head, nor do they have red meat and white fat. It would seem also that this scenario was different from the various decayed shark carcass sightings to which the scientists have compared it. Those other dead sharks floated ashore, while the Zuiyo Maru carcass was found 30 miles off the coast opposite Christchurch and was trawled off the bottom at a depth of 900 ft. The primary evidence given in favor of the basking shark identification was an analysis of the chemical composition of the horny fibers in the tissue sample. They matched elastoidin from a known basking shark. But the horny fibers are not themselves found in sharks!

A number of researchers who have studied the matter aren’t persuaded by the basking shark explanation. For example, Tokio Shikama, who was paleontology professor at Yokohama National University was convinced the remains were a plesiosaur. “Even if the tissue contains the same protein as the shark’s, it is rash to say that the monster is a shark. The finding is not enough to refute a speculation that the monster is a plesiosaur.” (Koster, John, “What was the New Zealand Monster? Oceans Magazine, 1977, pp. 56–59.) Dr. Fujiro Yasuda from Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology agreed with Shikama, saying “the photographs show the remains of a prehistoric animal.” (Sjögren, Bengt, Berömda vidunder, Settern, 1980.) After carefully reviewing the 1978 study, Malcolm Bowden wrote: “As I read this paper, it became clear that those who had later written on this subject and accepted the ‘basking shark’ identification had obtained almost all their evidence from this one document. However, when I examined it, I concluded that it was an extremely unsatisfactory review of the original evidence and was heavily biased in favour of the ‘basking shark’ identification from the beginning.” (Bowden, Malcolm, “The Japanese Carcass: A Plesiosaur-type Animal!,” Creation Science Movement, Portsmouth, UK.) One of the issues demonstrating the bias of those involved in the original “Collective Papers” report was the decision not to invite Yano (a graduate from the Yamaguchi Oceanological High School and the Assistant Production Manager of the Taiyo Fisheries) to their initial meeting which laid the groundwork for the study. Although they informally heard from him subsequently, he was never given the opportunity to make a presentation or submit a paper in defense of his conclusion.

A number of researchers who have studied the matter aren’t persuaded by the basking shark explanation. For example, Tokio Shikama, who was paleontology professor at Yokohama National University was convinced the remains were a plesiosaur. “Even if the tissue contains the same protein as the shark’s, it is rash to say that the monster is a shark. The finding is not enough to refute a speculation that the monster is a plesiosaur.” (Koster, John, “What was the New Zealand Monster? Oceans Magazine, 1977, pp. 56–59.) Dr. Fujiro Yasuda from Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology agreed with Shikama, saying “the photographs show the remains of a prehistoric animal.” (Sjögren, Bengt, Berömda vidunder, Settern, 1980.) After carefully reviewing the 1978 study, Malcolm Bowden wrote: “As I read this paper, it became clear that those who had later written on this subject and accepted the ‘basking shark’ identification had obtained almost all their evidence from this one document. However, when I examined it, I concluded that it was an extremely unsatisfactory review of the original evidence and was heavily biased in favour of the ‘basking shark’ identification from the beginning.” (Bowden, Malcolm, “The Japanese Carcass: A Plesiosaur-type Animal!,” Creation Science Movement, Portsmouth, UK.) One of the issues demonstrating the bias of those involved in the original “Collective Papers” report was the decision not to invite Yano (a graduate from the Yamaguchi Oceanological High School and the Assistant Production Manager of the Taiyo Fisheries) to their initial meeting which laid the groundwork for the study. Although they informally heard from him subsequently, he was never given the opportunity to make a presentation or submit a paper in defense of his conclusion.

The photos have given others pause regarding the basking shark interpretation. Creationist John Goertzen wrote an article stating that the shark identification relies on the presumption that the dorsal fin slipped into the wrong place as a result of decomposition. He presents the difficulties with this view, notes the eyewitness testimony regarding a pair of fins, and gives further evidence to support his conclusion that the creature was a marine tetrapod. (Goertzen, John, “New Zuiyo Maru Cryptid Observations-Strong Indications It Was a Marine Tetrapod,” CRSQ 38, June 2001, 19-29.) Look carefully at the picture to the left. As Bill Cooper observed, the cable is being bent by the shoulder bone. A shark bone would not be able to withstand that stress. (Cooper, Bill, “The Japanese Plesiosaur Reconsidered,” 7th European Creationist Conference, 2017.) Cooper moreover shows that a fair analysis of the photographs backs up the eye witness testimony that there was no dorsal fin present. He concludes that the this monster with its giant paddles is indeed a dead plesiosaur. If marine plesiosaurs really have survived till the present, then they could be the basis for many of the “sea monster” stories that have been written in modern times.

The photos have given others pause regarding the basking shark interpretation. Creationist John Goertzen wrote an article stating that the shark identification relies on the presumption that the dorsal fin slipped into the wrong place as a result of decomposition. He presents the difficulties with this view, notes the eyewitness testimony regarding a pair of fins, and gives further evidence to support his conclusion that the creature was a marine tetrapod. (Goertzen, John, “New Zuiyo Maru Cryptid Observations-Strong Indications It Was a Marine Tetrapod,” CRSQ 38, June 2001, 19-29.) Look carefully at the picture to the left. As Bill Cooper observed, the cable is being bent by the shoulder bone. A shark bone would not be able to withstand that stress. (Cooper, Bill, “The Japanese Plesiosaur Reconsidered,” 7th European Creationist Conference, 2017.) Cooper moreover shows that a fair analysis of the photographs backs up the eye witness testimony that there was no dorsal fin present. He concludes that the this monster with its giant paddles is indeed a dead plesiosaur. If marine plesiosaurs really have survived till the present, then they could be the basis for many of the “sea monster” stories that have been written in modern times.