Dinosaurian Coprolite & Fossil Skin

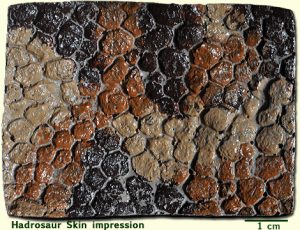

Coprolite is the scientific name for fossilized fecal material. To be even more blunt, we are talking about preserved dinosaur poop. Typically soft materials (like dinosaur skin, internal organs, and scat) are not fossilized. These tend to be easily destroyed in the process of dying, deformed by the burying sediments, decayed rapidly by bacteria, and scavenged by other animals. So typically all we have preserved from the great reptiles are the bones. But occasional exceptions have arisen, to the delight of paleontologists, as fossilized dinosaur skin (like the Hadrosaur skin impression on the right) and even droppings that were mineralized into rocks have been found.

Coprolite is the scientific name for fossilized fecal material. To be even more blunt, we are talking about preserved dinosaur poop. Typically soft materials (like dinosaur skin, internal organs, and scat) are not fossilized. These tend to be easily destroyed in the process of dying, deformed by the burying sediments, decayed rapidly by bacteria, and scavenged by other animals. So typically all we have preserved from the great reptiles are the bones. But occasional exceptions have arisen, to the delight of paleontologists, as fossilized dinosaur skin (like the Hadrosaur skin impression on the right) and even droppings that were mineralized into rocks have been found.

To the left is a wonderfully preserved dinosaur skin from a fossil Triceratops named Lane (photo by the Black Hills Institute of Geological Research). Amidst the scales are large protruding bumps, or rosettes, that match up well against some of the historical depictions of dinosaurs engraved on the Ica Stones. While these fossils typically still leave a lot of unanswered questions (like what colors the dinosaur was), they can give valuable clues to the general appearance and physiology of the great reptiles. For example, the evidence of fluffy hairs on some pterosaur fossils led to artistic revisions and provided further evidence that they warm-blooded.

To the left is a wonderfully preserved dinosaur skin from a fossil Triceratops named Lane (photo by the Black Hills Institute of Geological Research). Amidst the scales are large protruding bumps, or rosettes, that match up well against some of the historical depictions of dinosaurs engraved on the Ica Stones. While these fossils typically still leave a lot of unanswered questions (like what colors the dinosaur was), they can give valuable clues to the general appearance and physiology of the great reptiles. For example, the evidence of fluffy hairs on some pterosaur fossils led to artistic revisions and provided further evidence that they warm-blooded.

Fossilized scat is particularly interesting to modern cryptozoologists who hunt for possible living dinosaurian species. Droppings and footprints are often discovered and analyzed long before an elusive creature is photographed or captured. By comparing droppings found in a cryptid hotspot against an image like that at the lower left (The DinoWight Collection – Solnhofen Eichstätt Quarry), a researcher can determine if they are on the right track towards finding a possible living pterosaur. While pterosaur coprolite is rare, many pieces of mineralized dinosaur droppings have been found, some weighing up to hundreds of pounds. It seems that the pressure involved in a burial under watery sediments, along with the relaxation of bowel muscles quite often resulted in defecation at death.

A 2017 article entitled “Fossilized Poo Reveals that Vegetarian Dinosaurs had a Taste for Crabs” discusses coprolite research and the discovery of decaying wood and bits of crustaceans in sauropod droppings. (Witze, Alexandra, Scientific American) The paleontologists speculated that these dinosaurs might have been seeking the nutritious protein in burrowing insects and perhaps the calcium from shells. But this scenario fits better within the creation/flood model. Might these not be the same dinosaurs that made the fossilized tracks and established nesting sites on bedding planes, the ones we discussed in the previous page’s BEDS hypothesis? Perhaps these dinosaurs had survived the initial onslaught of Flood waves by swimming. But then they faced starvation, isolated on a sediment island. This might well have driven them to eating crabs and floating debris as a last resort. In 2020 a fossil of an ankylosaurus was analyzed and the discovery of a final meal in the gut made headlines. The remains included charcoal (maybe from impacts or volcanic debris), and vegetable matter typically from a late spring to summer timeframe. Is this evidence for the Flood date? Or was it an unending summer in the pre-Flood world?

Job 40:15 states that the mighty Behemoth eats grass like an ox. For many years, evolutionists did not believe that dinosaurs ate grass. They believed (as many museums and dinosaur books still claim) that grass didn’t evolve until about 55mya, approximately 11 years after the dinosaurs became extinct. But paleontologists began slicing coprolites for study under microscope. Researchers examining titanosaur coprolites were astonished to discover that dinosaurs ate at least five different types of grasses. Further investigation revealed that some dinosaurs even consumed rice. (Prasad, V., et al., “Late Cretaceous Origin of the Rice Tribe Provides Evidence for Early Diversification in Poaceae,” Nature Communications, 2011, p. 480.)